Sometimes, when you look at a function definition in Python, you might see that it takes two strange arguments: *args and **kwargs. If you’ve ever wondered what these peculiar variables are, or why your IDE defines them in main(), then this article is for you. You’ll learn how to use args and kwargs in Python to add more flexibility to your functions.

By the end of the article, you’ll know:

*args and **kwargs actually mean*args and **kwargs in function definitions*) to unpack iterables**) to unpack dictionariesThis article assumes that you already know how to define Python functions and work with lists and dictionaries.

Free Bonus: Click here to get a Python Cheat Sheet and learn the basics of Python 3, like working with data types, dictionaries, lists, and Python functions.

*args and **kwargs allow you to pass multiple arguments or keyword arguments to a function. Consider the following example. This is a simple function that takes two arguments and returns their sum:

def my_sum(a, b):

return a + b

This function works fine, but it’s limited to only two arguments. What if you need to sum a varying number of arguments, where the specific number of arguments passed is only determined at runtime? Wouldn’t it be great to create a function that could sum all the integers passed to it, no matter how many there are?

There are a few ways you can pass a varying number of arguments to a function. The first way is often the most intuitive for people that have experience with collections. You simply pass a list or a set of all the arguments to your function. So for my_sum(), you could pass a list of all the integers you need to add:

# sum_integers_list.py

def my_sum(my_integers):

result = 0

for x in my_integers:

result += x

return result

list_of_integers = [1, 2, 3]

print(my_sum(list_of_integers))

This implementation works, but whenever you call this function you’ll also need to create a list of arguments to pass to it. This can be inconvenient, especially if you don’t know up front all the values that should go into the list.

This is where *args can be really useful, because it allows you to pass a varying number of positional arguments. Take the following example:

# sum_integers_args.py

def my_sum(*args):

result = 0

# Iterating over the Python args tuple

for x in args:

result += x

return result

print(my_sum(1, 2, 3))

In this example, you’re no longer passing a list to my_sum(). Instead, you’re passing three different positional arguments. my_sum() takes all the parameters that are provided in the input and packs them all into a single iterable object named args.

Note that args is just a name. You’re not required to use the name args. You can choose any name that you prefer, such as integers:

# sum_integers_args_2.py

def my_sum(*integers):

result = 0

for x in integers:

result += x

return result

print(my_sum(1, 2, 3))

The function still works, even if you pass the iterable object as integers instead of args. All that matters here is that you use the unpacking operator (*).

Bear in mind that the iterable object you’ll get using the unpacking operator * is not a list but a tuple. A tuple is similar to a list in that they both support slicing and iteration. However, tuples are very different in at least one aspect: lists are mutable, while tuples are not. To test this, run the following code. This script tries to change a value of a list:

# change_list.py

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

my_list[0] = 9

print(my_list)

The value located at the very first index of the list should be updated to 9. If you execute this script, you will see that the list indeed gets modified:

$ python change_list.py

[9, 2, 3]

The first value is no longer 0, but the updated value 9. Now, try to do the same with a tuple:

# change_tuple.py

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3)

my_tuple[0] = 9

print(my_tuple)

Here, you see the same values, except they’re held together as a tuple. If you try to execute this script, you will see that the Python interpreter returns an error:

$ python change_tuple.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "change_tuple.py", line 3, in <module>

my_tuple[0] = 9

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

This is because a tuple is an immutable object, and its values cannot be changed after assignment. Keep this in mind when you’re working with tuples and *args.

Okay, now you’ve understood what *args is for, but what about **kwargs? **kwargs works just like *args, but instead of accepting positional arguments it accepts keyword (or named) arguments. Take the following example:

# concatenate.py

def concatenate(**kwargs):

result = ""

# Iterating over the Python kwargs dictionary

for arg in kwargs.values():

result += arg

return result

print(concatenate(a="Real", b="Python", c="Is", d="Great", e="!"))

When you execute the script above, concatenate() will iterate through the Python kwargs dictionary and concatenate all the values it finds:

$ python concatenate.py

RealPythonIsGreat!

Like args, kwargs is just a name that can be changed to whatever you want. Again, what is important here is the use of the unpacking operator (**).

So, the previous example could be written like this:

# concatenate_2.py

def concatenate(**words):

result = ""

for arg in words.values():

result += arg

return result

print(concatenate(a="Real", b="Python", c="Is", d="Great", e="!"))

Note that in the example above the iterable object is a standard dict. If you iterate over the dictionary and want to return its values, like in the example shown, then you must use .values().

In fact, if you forget to use this method, you will find yourself iterating through the keys of your Python kwargs dictionary instead, like in the following example:

# concatenate_keys.py

def concatenate(**kwargs):

result = ""

# Iterating over the keys of the Python kwargs dictionary

for arg in kwargs:

result += arg

return result

print(concatenate(a="Real", b="Python", c="Is", d="Great", e="!"))

Now, if you try to execute this example, you’ll notice the following output:

$ python concatenate_keys.py

abcde

As you can see, if you don’t specify .values(), your function will iterate over the keys of your Python kwargs dictionary, returning the wrong result.

Now that you have learned what *args and **kwargs are for, you are ready to start writing functions that take a varying number of input arguments. But what if you want to create a function that takes a changeable number of both positional and named arguments?

In this case, you have to bear in mind that order counts. Just as non-default arguments have to precede default arguments, so *args must come before **kwargs.

To recap, the correct order for your parameters is:

*args arguments**kwargs argumentsFor example, this function definition is correct:

# correct_function_definition.py

def my_function(a, b, *args, **kwargs):

pass

The *args variable is appropriately listed before **kwargs. But what if you try to modify the order of the arguments? For example, consider the following function:

# wrong_function_definition.py

def my_function(a, b, **kwargs, *args):

pass

Now, **kwargs comes before *args in the function definition. If you try to run this example, you’ll receive an error from the interpreter:

$ python wrong_function_definition.py

File "wrong_function_definition.py", line 2

def my_function(a, b, **kwargs, *args):

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

In this case, since *args comes after **kwargs, the Python interpreter throws a SyntaxError.

* & **You are now able to use *args and **kwargs to define Python functions that take a varying number of input arguments. Let’s go a little deeper to understand something more about the unpacking operators.

The single and double asterisk unpacking operators were introduced in Python 2. As of the 3.5 release, they have become even more powerful, thanks to PEP 448. In short, the unpacking operators are operators that unpack the values from iterable objects in Python. The single asterisk operator * can be used on any iterable that Python provides, while the double asterisk operator ** can only be used on dictionaries.

Let’s start with an example:

# print_list.py

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

print(my_list)

This code defines a list and then prints it to the standard output:

$ python print_list.py

[1, 2, 3]

Note how the list is printed, along with the corresponding brackets and commas.

Now, try to prepend the unpacking operator * to the name of your list:

# print_unpacked_list.py

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

print(*my_list)

Here, the * operator tells print() to unpack the list first.

In this case, the output is no longer the list itself, but rather the content of the list:

$ python print_unpacked_list.py

1 2 3

Can you see the difference between this execution and the one from print_list.py? Instead of a list, print() has taken three separate arguments as the input.

Another thing you’ll notice is that in print_unpacked_list.py, you used the unpacking operator * to call a function, instead of in a function definition. In this case, print() takes all the items of a list as though they were single arguments.

You can also use this method to call your own functions, but if your function requires a specific number of arguments, then the iterable you unpack must have the same number of arguments.

To test this behavior, consider this script:

# unpacking_call.py

def my_sum(a, b, c):

print(a + b + c)

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

my_sum(*my_list)

Here, my_sum() explicitly states that a, b, and c are required arguments.

If you run this script, you’ll get the sum of the three numbers in my_list:

$ python unpacking_call.py

6

The 3 elements in my_list match up perfectly with the required arguments in my_sum().

Now look at the following script, where my_list has 4 arguments instead of 3:

# wrong_unpacking_call.py

def my_sum(a, b, c):

print(a + b + c)

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4]

my_sum(*my_list)

In this example, my_sum() still expects just three arguments, but the * operator gets 4 items from the list. If you try to execute this script, you’ll see that the Python interpreter is unable to run it:

$ python wrong_unpacking_call.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "wrong_unpacking_call.py", line 6, in <module>

my_sum(*my_list)

TypeError: my_sum() takes 3 positional arguments but 4 were given

When you use the * operator to unpack a list and pass arguments to a function, it’s exactly as though you’re passing every single argument alone. This means that you can use multiple unpacking operators to get values from several lists and pass them all to a single function.

To test this behavior, consider the following example:

# sum_integers_args_3.py

def my_sum(*args):

result = 0

for x in args:

result += x

return result

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

list2 = [4, 5]

list3 = [6, 7, 8, 9]

print(my_sum(*list1, *list2, *list3))

If you run this example, all three lists are unpacked. Each individual item is passed to my_sum(), resulting in the following output:

$ python sum_integers_args_3.py

45

There are other convenient uses of the unpacking operator. For example, say you need to split a list into three different parts. The output should show the first value, the last value, and all the values in between. With the unpacking operator, you can do this in just one line of code:

# extract_list_body.py

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

a, *b, c = my_list

print(a)

print(b)

print(c)

In this example, my_list contains 6 items. The first variable is assigned to a, the last to c, and all other values are packed into a new list b. If you run the script, print() will show you that your three variables have the values you would expect:

$ python extract_list_body.py

1

[2, 3, 4, 5]

6

Another interesting thing you can do with the unpacking operator * is to split the items of any iterable object. This could be very useful if you need to merge two lists, for instance:

# merging_lists.py

my_first_list = [1, 2, 3]

my_second_list = [4, 5, 6]

my_merged_list = [*my_first_list, *my_second_list]

print(my_merged_list)

The unpacking operator * is prepended to both my_first_list and my_second_list.

If you run this script, you’ll see that the result is a merged list:

$ python merging_lists.py

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

You can even merge two different dictionaries by using the unpacking operator **:

# merging_dicts.py

my_first_dict = {"A": 1, "B": 2}

my_second_dict = {"C": 3, "D": 4}

my_merged_dict = {**my_first_dict, **my_second_dict}

print(my_merged_dict)

Here, the iterables to merge are my_first_dict and my_second_dict.

Executing this code outputs a merged dictionary:

$ python merging_dicts.py

{'A': 1, 'B': 2, 'C': 3, 'D': 4}

Remember that the * operator works on any iterable object. It can also be used to unpack a string:

# string_to_list.py

a = [*"RealPython"]

print(a)

In Python, strings are iterable objects, so * will unpack it and place all individual values in a list a:

$ python string_to_list.py

['R', 'e', 'a', 'l', 'P', 'y', 't', 'h', 'o', 'n']

The previous example seems great, but when you work with these operators it’s important to keep in mind the seventh rule of The Zen of Python by Tim Peters: Readability counts.

To see why, consider the following example:

# mysterious_statement.py

*a, = "RealPython"

print(a)

There’s the unpacking operator *, followed by a variable, a comma, and an assignment. That’s a lot packed into one line! In fact, this code is no different from the previous example. It just takes the string RealPython and assigns all the items to the new list a, thanks to the unpacking operator *.

The comma after the a does the trick. When you use the unpacking operator with variable assignment, Python requires that your resulting variable is either a list or a tuple. With the trailing comma, you have actually defined a tuple with just one named variable a.

While this is a neat trick, many Pythonistas would not consider this code to be very readable. As such, it’s best to use these kinds of constructions sparingly.

You are now able to use *args and **kwargs to accept a changeable number of arguments in your functions. You have also learned something more about the unpacking operators.

You’ve learned:

*args and **kwargs actually mean*args and **kwargs in function definitions*) to unpack iterables**) to unpack dictionariesIf you still have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out in the comments section below! To learn more about the use of the asterisks in Python, have a look at Trey Hunner’s article on the subject.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

# datePublished: #Wed Sep 4 14:00:00 2019# dateUpdated: #Wed Sep 4 14:00:00 2019# # Person begin #################### name: #Real Python# # Person end ###################### # Item end ######################## # Item begin ###################### id: #https://realpython.com/courses/lists-tuples-python/# title: #Lists and Tuples in Python# link: #https://realpython.com/courses/lists-tuples-python/# description: #In this course, you'll cover the important characteristics of lists and tuples in Python 3. You'll learn how to define them and how to manipulate them. When you're finished, you'll have a good feel for when and how to use these object types in a Python program.# content: #In this course, you’ll learn about working with lists and tuples. Lists and tuples are arguably Python’s most versatile, useful data types. You’ll find them in virtually every non-trivial Python program.

Here’s what you’ll learn in this tutorial: You’ll cover the important characteristics of lists and tuples. You’ll learn how to define them and how to manipulate them. When you’re finished, you’ll have a good feel for when and how to use these object types in a Python program.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “Python Lists and Tuples” quiz. Upon completion you will receive a score so you can track your learning progress over time:

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

# datePublished: #Tue Sep 3 14:00:00 2019# dateUpdated: #Tue Sep 3 14:00:00 2019# # Person begin #################### name: #Real Python# # Person end ###################### # Item end ######################## # Item begin ###################### id: #https://realpython.com/natural-language-processing-spacy-python/# title: #Natural Language Processing With spaCy in Python# link: #https://realpython.com/natural-language-processing-spacy-python/# description: #In this step-by-step tutorial, you'll learn how to use spaCy. This free and open-source library for Natural Language Processing (NLP) in Python has a lot of built-in capabilities and is becoming increasingly popular for processing and analyzing data in NLP.# content: #spaCy is a free and open-source library for Natural Language Processing (NLP) in Python with a lot of in-built capabilities. It’s becoming increasingly popular for processing and analyzing data in NLP. Unstructured textual data is produced at a large scale, and it’s important to process and derive insights from unstructured data. To do that, you need to represent the data in a format that can be understood by computers. NLP can help you do that.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn:

Free Bonus: Click here to get access to a chapter from Python Tricks: The Book that shows you Python's best practices with simple examples you can apply instantly to write more beautiful + Pythonic code.

NLP is a subfield of Artificial Intelligence and is concerned with interactions between computers and human languages. NLP is the process of analyzing, understanding, and deriving meaning from human languages for computers.

NLP helps you extract insights from unstructured text and has several use cases, such as:

spaCy is a free, open-source library for NLP in Python. It’s written in Cython and is designed to build information extraction or natural language understanding systems. It’s built for production use and provides a concise and user-friendly API.

In this section, you’ll install spaCy and then download data and models for the English language.

spaCy can be installed using pip, a Python package manager. You can use a virtual environment to avoid depending on system-wide packages. To learn more about virtual environments and pip, check out What Is Pip? A Guide for New Pythonistas and Python Virtual Environments: A Primer.

Create a new virtual environment:

$ python3 -m venv env

Activate this virtual environment and install spaCy:

$ source ./env/bin/activate

$ pip install spacy

spaCy has different types of models. The default model for the English language is en_core_web_sm.

Activate the virtual environment created in the previous step and download models and data for the English language:

$ python -m spacy download en_core_web_sm

Verify if the download was successful or not by loading it:

>>> import spacy

>>> nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

If the nlp object is created, then it means that spaCy was installed and that models and data were successfully downloaded.

In this section, you’ll use spaCy for a given input string and a text file. Load the language model instance in spaCy:

>>> import spacy

>>> nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

Here, the nlp object is a language model instance. You can assume that, throughout this tutorial, nlp refers to the language model loaded by en_core_web_sm. Now you can use spaCy to read a string or a text file.

You can use spaCy to create a processed Doc object, which is a container for accessing linguistic annotations, for a given input string:

>>> introduction_text = ('This tutorial is about Natural'

... ' Language Processing in Spacy.')

>>> introduction_doc = nlp(introduction_text)

>>> # Extract tokens for the given doc

>>> print ([token.text for token in introduction_doc])

['This', 'tutorial', 'is', 'about', 'Natural', 'Language',

'Processing', 'in', 'Spacy', '.']

In the above example, notice how the text is converted to an object that is understood by spaCy. You can use this method to convert any text into a processed Doc object and deduce attributes, which will be covered in the coming sections.

In this section, you’ll create a processed Doc object for a text file:

>>> file_name = 'introduction.txt'

>>> introduction_file_text = open(file_name).read()

>>> introduction_file_doc = nlp(introduction_file_text)

>>> # Extract tokens for the given doc

>>> print ([token.text for token in introduction_file_doc])

['This', 'tutorial', 'is', 'about', 'Natural', 'Language',

'Processing', 'in', 'Spacy', '.', '\n']

This is how you can convert a text file into a processed Doc object.

Note:

You can assume that:

_text are Unicode string objects._doc are spaCy’s language model objects.Sentence Detection is the process of locating the start and end of sentences in a given text. This allows you to you divide a text into linguistically meaningful units. You’ll use these units when you’re processing your text to perform tasks such as part of speech tagging and entity extraction.

In spaCy, the sents property is used to extract sentences. Here’s how you would extract the total number of sentences and the sentences for a given input text:

>>> about_text = ('Gus Proto is a Python developer currently'

... ' working for a London-based Fintech'

... ' company. He is interested in learning'

... ' Natural Language Processing.')

>>> about_doc = nlp(about_text)

>>> sentences = list(about_doc.sents)

>>> len(sentences)

2

>>> for sentence in sentences:

... print (sentence)

...

'Gus Proto is a Python developer currently working for a

London-based Fintech company.'

'He is interested in learning Natural Language Processing.'

In the above example, spaCy is correctly able to identify sentences in the English language, using a full stop(.) as the sentence delimiter. You can also customize the sentence detection to detect sentences on custom delimiters.

Here’s an example, where an ellipsis(...) is used as the delimiter:

>>> def set_custom_boundaries(doc):

... # Adds support to use `...` as the delimiter for sentence detection

... for token in doc[:-1]:

... if token.text == '...':

... doc[token.i+1].is_sent_start = True

... return doc

...

>>> ellipsis_text = ('Gus, can you, ... never mind, I forgot'

... ' what I was saying. So, do you think'

... ' we should ...')

>>> # Load a new model instance

>>> custom_nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

>>> custom_nlp.add_pipe(set_custom_boundaries, before='parser')

>>> custom_ellipsis_doc = custom_nlp(ellipsis_text)

>>> custom_ellipsis_sentences = list(custom_ellipsis_doc.sents)

>>> for sentence in custom_ellipsis_sentences:

... print(sentence)

...

Gus, can you, ...

never mind, I forgot what I was saying.

So, do you think we should ...

>>> # Sentence Detection with no customization

>>> ellipsis_doc = nlp(ellipsis_text)

>>> ellipsis_sentences = list(ellipsis_doc.sents)

>>> for sentence in ellipsis_sentences:

... print(sentence)

...

Gus, can you, ... never mind, I forgot what I was saying.

So, do you think we should ...

Note that custom_ellipsis_sentences contain three sentences, whereas ellipsis_sentences contains two sentences. These sentences are still obtained via the sents attribute, as you saw before.

Tokenization is the next step after sentence detection. It allows you to identify the basic units in your text. These basic units are called tokens. Tokenization is useful because it breaks a text into meaningful units. These units are used for further analysis, like part of speech tagging.

In spaCy, you can print tokens by iterating on the Doc object:

>>> for token in about_doc:

... print (token, token.idx)

...

Gus 0

Proto 4

is 10

a 13

Python 15

developer 22

currently 32

working 42

for 50

a 54

London 56

- 62

based 63

Fintech 69

company 77

. 84

He 86

is 89

interested 92

in 103

learning 106

Natural 115

Language 123

Processing 132

. 142

Note how spaCy preserves the starting index of the tokens. It’s useful for in-place word replacement. spaCy provides various attributes for the Token class:

>>> for token in about_doc:

... print (token, token.idx, token.text_with_ws,

... token.is_alpha, token.is_punct, token.is_space,

... token.shape_, token.is_stop)

...

Gus 0 Gus True False False Xxx False

Proto 4 Proto True False False Xxxxx False

is 10 is True False False xx True

a 13 a True False False x True

Python 15 Python True False False Xxxxx False

developer 22 developer True False False xxxx False

currently 32 currently True False False xxxx False

working 42 working True False False xxxx False

for 50 for True False False xxx True

a 54 a True False False x True

London 56 London True False False Xxxxx False

- 62 - False True False - False

based 63 based True False False xxxx False

Fintech 69 Fintech True False False Xxxxx False

company 77 company True False False xxxx False

. 84 . False True False . False

He 86 He True False False Xx True

is 89 is True False False xx True

interested 92 interested True False False xxxx False

in 103 in True False False xx True

learning 106 learning True False False xxxx False

Natural 115 Natural True False False Xxxxx False

Language 123 Language True False False Xxxxx False

Processing 132 Processing True False False Xxxxx False

. 142 . False True False . False

In this example, some of the commonly required attributes are accessed:

text_with_ws prints token text with trailing space (if present).is_alpha detects if the token consists of alphabetic characters or not.is_punct detects if the token is a punctuation symbol or not.is_space detects if the token is a space or not.shape_ prints out the shape of the word.is_stop detects if the token is a stop word or not.Note: You’ll learn more about stop words in the next section.

You can also customize the tokenization process to detect tokens on custom characters. This is often used for hyphenated words, which are words joined with hyphen. For example, “London-based” is a hyphenated word.

spaCy allows you to customize tokenization by updating the tokenizer property on the nlp object:

>>> import re

>>> import spacy

>>> from spacy.tokenizer import Tokenizer

>>> custom_nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

>>> prefix_re = spacy.util.compile_prefix_regex(custom_nlp.Defaults.prefixes)

>>> suffix_re = spacy.util.compile_suffix_regex(custom_nlp.Defaults.suffixes)

>>> infix_re = re.compile(r'''[-~]''')

>>> def customize_tokenizer(nlp):

... # Adds support to use `-` as the delimiter for tokenization

... return Tokenizer(nlp.vocab, prefix_search=prefix_re.search,

... suffix_search=suffix_re.search,

... infix_finditer=infix_re.finditer,

... token_match=None

... )

...

>>> custom_nlp.tokenizer = customize_tokenizer(custom_nlp)

>>> custom_tokenizer_about_doc = custom_nlp(about_text)

>>> print([token.text for token in custom_tokenizer_about_doc])

['Gus', 'Proto', 'is', 'a', 'Python', 'developer', 'currently',

'working', 'for', 'a', 'London', '-', 'based', 'Fintech',

'company', '.', 'He', 'is', 'interested', 'in', 'learning',

'Natural', 'Language', 'Processing', '.']

In order for you to customize, you can pass various parameters to the Tokenizer class:

nlp.vocab is a storage container for special cases and is used to handle cases like contractions and emoticons.prefix_search is the function that is used to handle preceding punctuation, such as opening parentheses.infix_finditer is the function that is used to handle non-whitespace separators, such as hyphens.suffix_search is the function that is used to handle succeeding punctuation, such as closing parentheses.token_match is an optional boolean function that is used to match strings that should never be split. It overrides the previous rules and is useful for entities like URLs or numbers.Note: spaCy already detects hyphenated words as individual tokens. The above code is just an example to show how tokenization can be customized. It can be used for any other character.

Stop words are the most common words in a language. In the English language, some examples of stop words are the, are, but, and they. Most sentences need to contain stop words in order to be full sentences that make sense.

Generally, stop words are removed because they aren’t significant and distort the word frequency analysis. spaCy has a list of stop words for the English language:

>>> import spacy

>>> spacy_stopwords = spacy.lang.en.stop_words.STOP_WORDS

>>> len(spacy_stopwords)

326

>>> for stop_word in list(spacy_stopwords)[:10]:

... print(stop_word)

...

using

becomes

had

itself

once

often

is

herein

who

too

You can remove stop words from the input text:

>>> for token in about_doc:

... if not token.is_stop:

... print (token)

...

Gus

Proto

Python

developer

currently

working

London

-

based

Fintech

company

.

interested

learning

Natural

Language

Processing

.

Stop words like is, a, for, the, and in are not printed in the output above. You can also create a list of tokens not containing stop words:

>>> about_no_stopword_doc = [token for token in about_doc if not token.is_stop]

>>> print (about_no_stopword_doc)

[Gus, Proto, Python, developer, currently, working, London,

-, based, Fintech, company, ., interested, learning, Natural,

Language, Processing, .]

about_no_stopword_doc can be joined with spaces to form a sentence with no stop words.

Lemmatization is the process of reducing inflected forms of a word while still ensuring that the reduced form belongs to the language. This reduced form or root word is called a lemma.

For example, organizes, organized and organizing are all forms of organize. Here, organize is the lemma. The inflection of a word allows you to express different grammatical categories like tense (organized vs organize), number (trains vs train), and so on. Lemmatization is necessary because it helps you reduce the inflected forms of a word so that they can be analyzed as a single item. It can also help you normalize the text.

spaCy has the attribute lemma_ on the Token class. This attribute has the lemmatized form of a token:

>>> conference_help_text = ('Gus is helping organize a developer'

... 'conference on Applications of Natural Language'

... ' Processing. He keeps organizing local Python meetups'

... ' and several internal talks at his workplace.')

>>> conference_help_doc = nlp(conference_help_text)

>>> for token in conference_help_doc:

... print (token, token.lemma_)

...

Gus Gus

is be

helping help

organize organize

a a

developer developer

conference conference

on on

Applications Applications

of of

Natural Natural

Language Language

Processing Processing

. .

He -PRON-

keeps keep

organizing organize

local local

Python Python

meetups meetup

and and

several several

internal internal

talks talk

at at

his -PRON-

workplace workplace

. .

In this example, organizing reduces to its lemma form organize. If you do not lemmatize the text, then organize and organizing will be counted as different tokens, even though they both have a similar meaning. Lemmatization helps you avoid duplicate words that have similar meanings.

You can now convert a given text into tokens and perform statistical analysis over it. This analysis can give you various insights about word patterns, such as common words or unique words in the text:

>>> from collections import Counter

>>> complete_text = ('Gus Proto is a Python developer currently'

... 'working for a London-based Fintech company. He is'

... ' interested in learning Natural Language Processing.'

... ' There is a developer conference happening on 21 July'

... ' 2019 in London. It is titled "Applications of Natural'

... ' Language Processing". There is a helpline number '

... ' available at +1-1234567891. Gus is helping organize it.'

... ' He keeps organizing local Python meetups and several'

... ' internal talks at his workplace. Gus is also presenting'

... ' a talk. The talk will introduce the reader about "Use'

... ' cases of Natural Language Processing in Fintech".'

... ' Apart from his work, he is very passionate about music.'

... ' Gus is learning to play the Piano. He has enrolled '

... ' himself in the weekend batch of Great Piano Academy.'

... ' Great Piano Academy is situated in Mayfair or the City'

... ' of London and has world-class piano instructors.')

...

>>> complete_doc = nlp(complete_text)

>>> # Remove stop words and punctuation symbols

>>> words = [token.text for token in complete_doc

... if not token.is_stop and not token.is_punct]

>>> word_freq = Counter(words)

>>> # 5 commonly occurring words with their frequencies

>>> common_words = word_freq.most_common(5)

>>> print (common_words)

[('Gus', 4), ('London', 3), ('Natural', 3), ('Language', 3), ('Processing', 3)]

>>> # Unique words

>>> unique_words = [word for (word, freq) in word_freq.items() if freq == 1]

>>> print (unique_words)

['Proto', 'currently', 'working', 'based', 'company',

'interested', 'conference', 'happening', '21', 'July',

'2019', 'titled', 'Applications', 'helpline', 'number',

'available', '+1', '1234567891', 'helping', 'organize',

'keeps', 'organizing', 'local', 'meetups', 'internal',

'talks', 'workplace', 'presenting', 'introduce', 'reader',

'Use', 'cases', 'Apart', 'work', 'passionate', 'music', 'play',

'enrolled', 'weekend', 'batch', 'situated', 'Mayfair', 'City',

'world', 'class', 'piano', 'instructors']

By looking at the common words, you can see that the text as a whole is probably about Gus, London, or Natural Language Processing. This way, you can take any unstructured text and perform statistical analysis to know what it’s about.

Here’s another example of the same text with stop words:

>>> words_all = [token.text for token in complete_doc if not token.is_punct]

>>> word_freq_all = Counter(words_all)

>>> # 5 commonly occurring words with their frequencies

>>> common_words_all = word_freq_all.most_common(5)

>>> print (common_words_all)

[('is', 10), ('a', 5), ('in', 5), ('Gus', 4), ('of', 4)]

Four out of five of the most common words are stop words, which don’t tell you much about the text. If you consider stop words while doing word frequency analysis, then you won’t be able to derive meaningful insights from the input text. This is why removing stop words is so important.

Part of speech or POS is a grammatical role that explains how a particular word is used in a sentence. There are eight parts of speech:

Part of speech tagging is the process of assigning a POS tag to each token depending on its usage in the sentence. POS tags are useful for assigning a syntactic category like noun or verb to each word.

In spaCy, POS tags are available as an attribute on the Token object:

>>> for token in about_doc:

... print (token, token.tag_, token.pos_, spacy.explain(token.tag_))

...

Gus NNP PROPN noun, proper singular

Proto NNP PROPN noun, proper singular

is VBZ VERB verb, 3rd person singular present

a DT DET determiner

Python NNP PROPN noun, proper singular

developer NN NOUN noun, singular or mass

currently RB ADV adverb

working VBG VERB verb, gerund or present participle

for IN ADP conjunction, subordinating or preposition

a DT DET determiner

London NNP PROPN noun, proper singular

- HYPH PUNCT punctuation mark, hyphen

based VBN VERB verb, past participle

Fintech NNP PROPN noun, proper singular

company NN NOUN noun, singular or mass

. . PUNCT punctuation mark, sentence closer

He PRP PRON pronoun, personal

is VBZ VERB verb, 3rd person singular present

interested JJ ADJ adjective

in IN ADP conjunction, subordinating or preposition

learning VBG VERB verb, gerund or present participle

Natural NNP PROPN noun, proper singular

Language NNP PROPN noun, proper singular

Processing NNP PROPN noun, proper singular

. . PUNCT punctuation mark, sentence closer

Here, two attributes of the Token class are accessed:

tag_ lists the fine-grained part of speech.pos_ lists the coarse-grained part of speech.spacy.explain gives descriptive details about a particular POS tag. spaCy provides a complete tag list along with an explanation for each tag.

Using POS tags, you can extract a particular category of words:

>>> nouns = []

>>> adjectives = []

>>> for token in about_doc:

... if token.pos_ == 'NOUN':

... nouns.append(token)

... if token.pos_ == 'ADJ':

... adjectives.append(token)

...

>>> nouns

[developer, company]

>>> adjectives

[interested]

You can use this to derive insights, remove the most common nouns, or see which adjectives are used for a particular noun.

spaCy comes with a built-in visualizer called displaCy. You can use it to visualize a dependency parse or named entities in a browser or a Jupyter notebook.

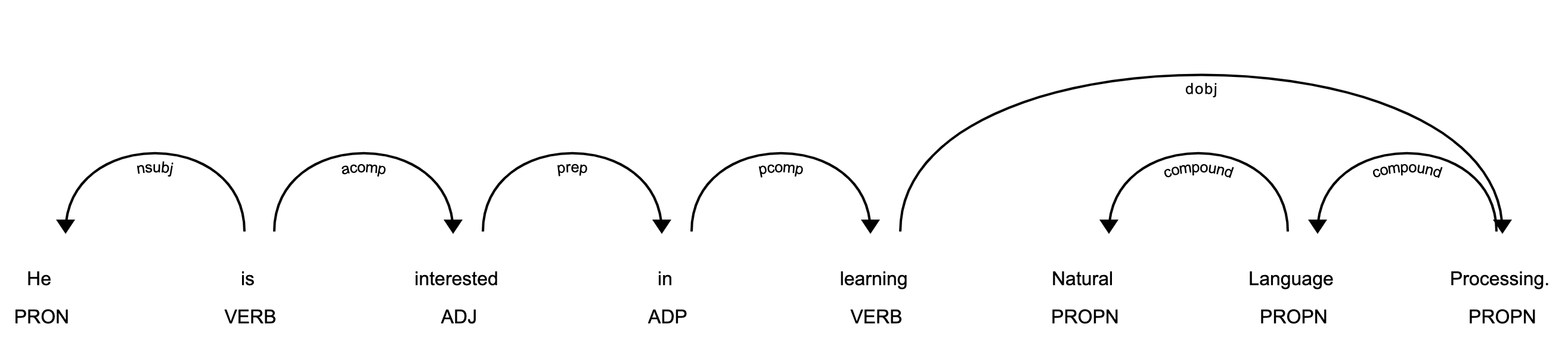

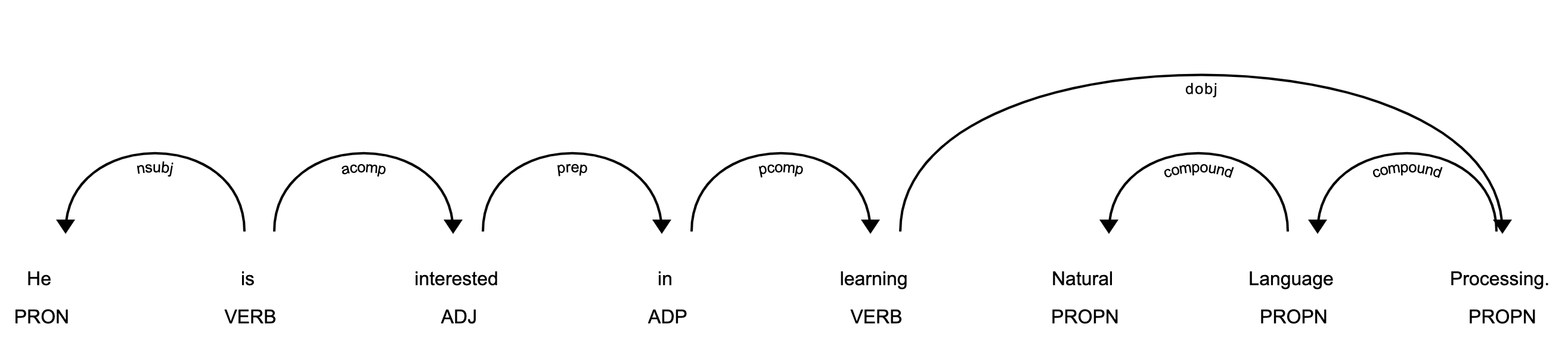

You can use displaCy to find POS tags for tokens:

>>> from spacy import displacy

>>> about_interest_text = ('He is interested in learning'

... ' Natural Language Processing.')

>>> about_interest_doc = nlp(about_interest_text)

>>> displacy.serve(about_interest_doc, style='dep')

The above code will spin a simple web server. You can see the visualization by opening http://127.0.0.1:5000 in your browser:

In the image above, each token is assigned a POS tag written just below the token.

Note: Here’s how you can use displaCy in a Jupyter notebook:

>>> displacy.render(about_interest_doc, style='dep', jupyter=True)

You can create a preprocessing function that takes text as input and applies the following operations:

A preprocessing function converts text to an analyzable format. It’s necessary for most NLP tasks. Here’s an example:

>>> def is_token_allowed(token):

... '''

... Only allow valid tokens which are not stop words

... and punctuation symbols.

... '''

... if (not token or not token.string.strip() or

... token.is_stop or token.is_punct):

... return False

... return True

...

>>> def preprocess_token(token):

... # Reduce token to its lowercase lemma form

... return token.lemma_.strip().lower()

...

>>> complete_filtered_tokens = [preprocess_token(token)

... for token in complete_doc if is_token_allowed(token)]

>>> complete_filtered_tokens

['gus', 'proto', 'python', 'developer', 'currently', 'work',

'london', 'base', 'fintech', 'company', 'interested', 'learn',

'natural', 'language', 'processing', 'developer', 'conference',

'happen', '21', 'july', '2019', 'london', 'title',

'applications', 'natural', 'language', 'processing', 'helpline',

'number', 'available', '+1', '1234567891', 'gus', 'help',

'organize', 'keep', 'organize', 'local', 'python', 'meetup',

'internal', 'talk', 'workplace', 'gus', 'present', 'talk', 'talk',

'introduce', 'reader', 'use', 'case', 'natural', 'language',

'processing', 'fintech', 'apart', 'work', 'passionate', 'music',

'gus', 'learn', 'play', 'piano', 'enrol', 'weekend', 'batch',

'great', 'piano', 'academy', 'great', 'piano', 'academy',

'situate', 'mayfair', 'city', 'london', 'world', 'class',

'piano', 'instructor']

Note that the complete_filtered_tokens does not contain any stop word or punctuation symbols and consists of lemmatized lowercase tokens.

Rule-based matching is one of the steps in extracting information from unstructured text. It’s used to identify and extract tokens and phrases according to patterns (such as lowercase) and grammatical features (such as part of speech).

Rule-based matching can use regular expressions to extract entities (such as phone numbers) from an unstructured text. It’s different from extracting text using regular expressions only in the sense that regular expressions don’t consider the lexical and grammatical attributes of the text.

With rule-based matching, you can extract a first name and a last name, which are always proper nouns:

>>> from spacy.matcher import Matcher

>>> matcher = Matcher(nlp.vocab)

>>> def extract_full_name(nlp_doc):

... pattern = [{'POS': 'PROPN'}, {'POS': 'PROPN'}]

... matcher.add('FULL_NAME', None, pattern)

... matches = matcher(nlp_doc)

... for match_id, start, end in matches:

... span = nlp_doc[start:end]

... return span.text

...

>>> extract_full_name(about_doc)

'Gus Proto'

In this example, pattern is a list of objects that defines the combination of tokens to be matched. Both POS tags in it are PROPN (proper noun). So, the pattern consists of two objects in which the POS tags for both tokens should be PROPN. This pattern is then added to Matcher using FULL_NAME and the the match_id. Finally, matches are obtained with their starting and end indexes.

You can also use rule-based matching to extract phone numbers:

>>> from spacy.matcher import Matcher

>>> matcher = Matcher(nlp.vocab)

>>> conference_org_text = ('There is a developer conference'

... 'happening on 21 July 2019 in London. It is titled'

... ' "Applications of Natural Language Processing".'

... ' There is a helpline number available'

... ' at (123) 456-789')

...

>>> def extract_phone_number(nlp_doc):

... pattern = [{'ORTH': '('}, {'SHAPE': 'ddd'},

... {'ORTH': ')'}, {'SHAPE': 'ddd'},

... {'ORTH': '-', 'OP': '?'},

... {'SHAPE': 'ddd'}]

... matcher.add('PHONE_NUMBER', None, pattern)

... matches = matcher(nlp_doc)

... for match_id, start, end in matches:

... span = nlp_doc[start:end]

... return span.text

...

>>> conference_org_doc = nlp(conference_org_text)

>>> extract_phone_number(conference_org_doc)

'(123) 456-789'

In this example, only the pattern is updated in order to match phone numbers from the previous example. Here, some attributes of the token are also used:

ORTH gives the exact text of the token.SHAPE transforms the token string to show orthographic features.OP defines operators. Using ? as a value means that the pattern is optional, meaning it can match 0 or 1 times.Note: For simplicity, phone numbers are assumed to be of a particular format: (123) 456-789. You can change this depending on your use case.

Rule-based matching helps you identify and extract tokens and phrases according to lexical patterns (such as lowercase) and grammatical features(such as part of speech).

Dependency parsing is the process of extracting the dependency parse of a sentence to represent its grammatical structure. It defines the dependency relationship between headwords and their dependents. The head of a sentence has no dependency and is called the root of the sentence. The verb is usually the head of the sentence. All other words are linked to the headword.

The dependencies can be mapped in a directed graph representation:

Dependency parsing helps you know what role a word plays in the text and how different words relate to each other. It’s also used in shallow parsing and named entity recognition.

Here’s how you can use dependency parsing to see the relationships between words:

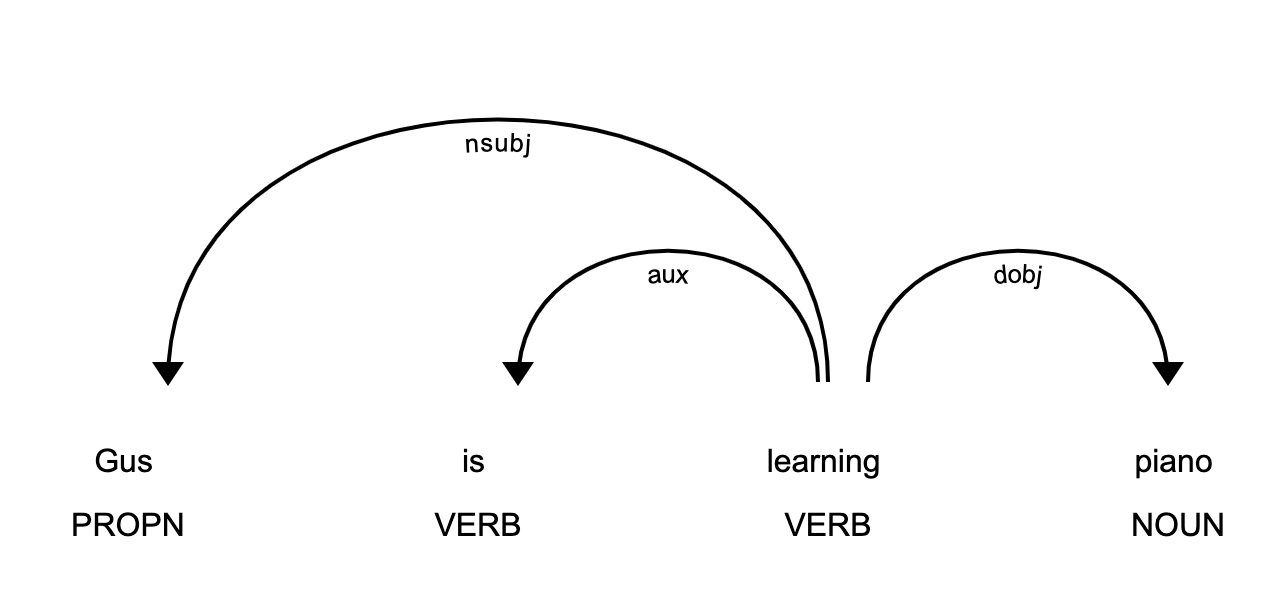

>>> piano_text = 'Gus is learning piano'

>>> piano_doc = nlp(piano_text)

>>> for token in piano_doc:

... print (token.text, token.tag_, token.head.text, token.dep_)

...

Gus NNP learning nsubj

is VBZ learning aux

learning VBG learning ROOT

piano NN learning dobj

In this example, the sentence contains three relationships:

nsubj is the subject of the word. Its headword is a verb.aux is an auxiliary word. Its headword is a verb.dobj is the direct object of the verb. Its headword is a verb.There is a detailed list of relationships with descriptions. You can use displaCy to visualize the dependency tree:

>>> displacy.serve(piano_doc, style='dep')

This code will produce a visualization that can be accessed by opening http://127.0.0.1:5000 in your browser:

This image shows you that the subject of the sentence is the proper noun Gus and that it has a learn relationship with piano.

The dependency parse tree has all the properties of a tree. This tree contains information about sentence structure and grammar and can be traversed in different ways to extract relationships.

spaCy provides attributes like children, lefts, rights, and subtree to navigate the parse tree:

>>> one_line_about_text = ('Gus Proto is a Python developer'

... ' currently working for a London-based Fintech company')

>>> one_line_about_doc = nlp(one_line_about_text)

>>> # Extract children of `developer`

>>> print([token.text for token in one_line_about_doc[5].children])

['a', 'Python', 'working']

>>> # Extract previous neighboring node of `developer`

>>> print (one_line_about_doc[5].nbor(-1))

Python

>>> # Extract next neighboring node of `developer`

>>> print (one_line_about_doc[5].nbor())

currently

>>> # Extract all tokens on the left of `developer`

>>> print([token.text for token in one_line_about_doc[5].lefts])

['a', 'Python']

>>> # Extract tokens on the right of `developer`

>>> print([token.text for token in one_line_about_doc[5].rights])

['working']

>>> # Print subtree of `developer`

>>> print (list(one_line_about_doc[5].subtree))

[a, Python, developer, currently, working, for, a, London, -,

based, Fintech, company]

You can construct a function that takes a subtree as an argument and returns a string by merging words in it:

>>> def flatten_tree(tree):

... return ''.join([token.text_with_ws for token in list(tree)]).strip()

...

>>> # Print flattened subtree of `developer`

>>> print (flatten_tree(one_line_about_doc[5].subtree))

a Python developer currently working for a London-based Fintech company

You can use this function to print all the tokens in a subtree.

Shallow parsing, or chunking, is the process of extracting phrases from unstructured text. Chunking groups adjacent tokens into phrases on the basis of their POS tags. There are some standard well-known chunks such as noun phrases, verb phrases, and prepositional phrases.

A noun phrase is a phrase that has a noun as its head. It could also include other kinds of words, such as adjectives, ordinals, determiners. Noun phrases are useful for explaining the context of the sentence. They help you infer what is being talked about in the sentence.

spaCy has the property noun_chunks on Doc object. You can use it to extract noun phrases:

>>> conference_text = ('There is a developer conference'

... ' happening on 21 July 2019 in London.')

>>> conference_doc = nlp(conference_text)

>>> # Extract Noun Phrases

>>> for chunk in conference_doc.noun_chunks:

... print (chunk)

...

a developer conference

21 July

London

By looking at noun phrases, you can get information about your text. For example, a developer conference indicates that the text mentions a conference, while the date 21 July lets you know that conference is scheduled for 21 July. You can figure out whether the conference is in the past or the future. London tells you that the conference is in London.

A verb phrase is a syntactic unit composed of at least one verb. This verb can be followed by other chunks, such as noun phrases. Verb phrases are useful for understanding the actions that nouns are involved in.

spaCy has no built-in functionality to extract verb phrases, so you’ll need a library called textacy:

Note:

You can use pip to install textacy:

$ pip install textacy

Now that you have textacy installed, you can use it to extract verb phrases based on grammar rules:

>>> import textacy

>>> about_talk_text = ('The talk will introduce reader about Use'

... ' cases of Natural Language Processing in'

... ' Fintech')

>>> pattern = r'(<VERB>?<ADV>*<VERB>+)'

>>> about_talk_doc = textacy.make_spacy_doc(about_talk_text,

... lang='en_core_web_sm')

>>> verb_phrases = textacy.extract.pos_regex_matches(about_talk_doc, pattern)

>>> # Print all Verb Phrase

>>> for chunk in verb_phrases:

... print(chunk.text)

...

will introduce

>>> # Extract Noun Phrase to explain what nouns are involved

>>> for chunk in about_talk_doc.noun_chunks:

... print (chunk)

...

The talk

reader

Use cases

Natural Language Processing

Fintech

In this example, the verb phrase introduce indicates that something will be introduced. By looking at noun phrases, you can see that there is a talk that will introduce the reader to use cases of Natural Language Processing or Fintech.

The above code extracts all the verb phrases using a regular expression pattern of POS tags. You can tweak the pattern for verb phrases depending upon your use case.

Note: In the previous example, you could have also done dependency parsing to see what the relationships between the words were.

Named Entity Recognition (NER) is the process of locating named entities in unstructured text and then classifying them into pre-defined categories, such as person names, organizations, locations, monetary values, percentages, time expressions, and so on.

You can use NER to know more about the meaning of your text. For example, you could use it to populate tags for a set of documents in order to improve the keyword search. You could also use it to categorize customer support tickets into relevant categories.

spaCy has the property ents on Doc objects. You can use it to extract named entities:

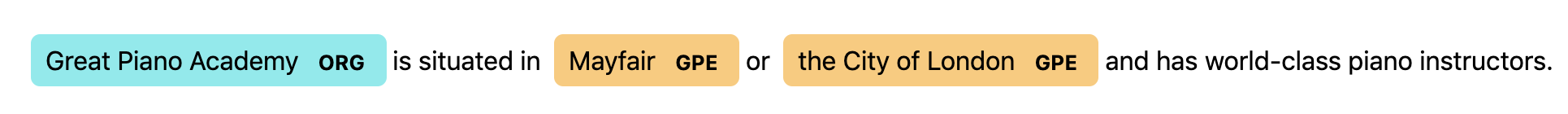

>>> piano_class_text = ('Great Piano Academy is situated'

... ' in Mayfair or the City of London and has'

... ' world-class piano instructors.')

>>> piano_class_doc = nlp(piano_class_text)

>>> for ent in piano_class_doc.ents:

... print(ent.text, ent.start_char, ent.end_char,

... ent.label_, spacy.explain(ent.label_))

...

Great Piano Academy 0 19 ORG Companies, agencies, institutions, etc.

Mayfair 35 42 GPE Countries, cities, states

the City of London 46 64 GPE Countries, cities, states

In the above example, ent is a Span object with various attributes:

text gives the Unicode text representation of the entity.start_char denotes the character offset for the start of the entity.end_char denotes the character offset for the end of the entity.label_ gives the label of the entity.spacy.explain gives descriptive details about an entity label. The spaCy model has a pre-trained list of entity classes. You can use displaCy to visualize these entities:

>>> displacy.serve(piano_class_doc, style='ent')

If you open http://127.0.0.1:5000 in your browser, then you can see the visualization:

You can use NER to redact people’s names from a text. For example, you might want to do this in order to hide personal information collected in a survey. You can use spaCy to do that:

>>> survey_text = ('Out of 5 people surveyed, James Robert,'

... ' Julie Fuller and Benjamin Brooks like'

... ' apples. Kelly Cox and Matthew Evans'

... ' like oranges.')

...

>>> def replace_person_names(token):

... if token.ent_iob != 0 and token.ent_type_ == 'PERSON':

... return '[REDACTED] '

... return token.string

...

>>> def redact_names(nlp_doc):

... for ent in nlp_doc.ents:

... ent.merge()

... tokens = map(replace_person_names, nlp_doc)

... return ''.join(tokens)

...

>>> survey_doc = nlp(survey_text)

>>> redact_names(survey_doc)

'Out of 5 people surveyed, [REDACTED] , [REDACTED] and'

' [REDACTED] like apples. [REDACTED] and [REDACTED]'

' like oranges.'

In this example, replace_person_names() uses ent_iob. It gives the IOB code of the named entity tag using inside-outside-beginning (IOB) tagging. Here, it can assume a value other than zero, because zero means that no entity tag is set.

spaCy is a powerful and advanced library that is gaining huge popularity for NLP applications due to its speed, ease of use, accuracy, and extensibility. Congratulations! You now know:

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

# datePublished: #Mon Sep 2 14:00:00 2019# dateUpdated: #Mon Sep 2 14:00:00 2019# # Person begin #################### name: #Real Python# # Person end ###################### # Item end ######################## # Item begin ###################### id: #https://realpython.com/pycharm-guide/# title: #PyCharm for Productive Python Development (Guide)# link: #https://realpython.com/pycharm-guide/# description: #In this step-by-step tutorial, you'll learn how you can use PyCharm to be a more productive Python developer. PyCharm makes debugging and visualization easy so you can focus on business logic and just get the job done.# content: #As a programmer, you should be focused on the business logic and creating useful applications for your users. In doing that, PyCharm by JetBrains saves you a lot of time by taking care of the routine and by making a number of other tasks such as debugging and visualization easy.

In this article, you’ll learn about:

This article assumes that you’re familiar with Python development and already have some form of Python installed on your system. Python 3.6 will be used for this tutorial. Screenshots and demos provided are for macOS. Because PyCharm runs on all major platforms, you may see slightly different UI elements and may need to modify certain commands.

Note:

PyCharm comes in three editions:

For more details on their differences, check out the PyCharm Editions Comparison Matrix by JetBrains. The company also has special offers for students, teachers, open source projects, and other cases.

Clone Repo: Click here to clone the repo you'll use to explore the project-focused features of PyCharm in this tutorial.

This article will use PyCharm Community Edition 2019.1 as it’s free and available on every major platform. Only the section about the professional features will use PyCharm Professional Edition 2019.1.

The recommended way of installing PyCharm is with the JetBrains Toolbox App. With its help, you’ll be able to install different JetBrains products or several versions of the same product, update, rollback, and easily remove any tool when necessary. You’ll also be able to quickly open any project in the right IDE and version.

To install the Toolbox App, refer to the documentation by JetBrains. It will automatically give you the right instructions depending on your OS. In case it didn’t recognize your OS correctly, you can always find it from the drop down list on the top right section:

After installing, launch the app and accept the user agreement. Under the Tools tab, you’ll see a list of available products. Find PyCharm Community there and click Install:

Voilà! You have PyCharm available on your machine. If you don’t want to use the Toolbox app, then you can also do a stand-alone installation of PyCharm.

Launch PyCharm, and you’ll see the import settings popup:

PyCharm will automatically detect that this is a fresh install and choose Do not import settings for you. Click OK, and PyCharm will ask you to select a keymap scheme. Leave the default and click Next: UI Themes on the bottom right:

PyCharm will then ask you to choose a dark theme called Darcula or a light theme. Choose whichever you prefer and click Next: Launcher Script:

I’ll be using the dark theme Darcula throughout this tutorial. You can find and install other themes as plugins, or you can also import them.

On the next page, leave the defaults and click Next: Featured plugins. There, PyCharm will show you a list of plugins you may want to install because most users like to use them. Click Start using PyCharm, and now you are ready to write some code!

In PyCharm, you do everything in the context of a project. Thus, the first thing you need to do is create one.

After installing and opening PyCharm, you are on the welcome screen. Click Create New Project, and you’ll see the New Project popup:

Specify the project location and expand the Project Interpreter drop down. Here, you have options to create a new project interpreter or reuse an existing one. Choose New environment using. Right next to it, you have a drop down list to select one of Virtualenv, Pipenv, or Conda, which are the tools that help to keep dependencies required by different projects separate by creating isolated Python environments for them.

You are free to select whichever you like, but Virtualenv is used for this tutorial. If you choose to, you can specify the environment location and choose the base interpreter from the list, which is a list of Python interpreters (such as Python2.7 and Python3.6) installed on your system. Usually, the defaults are fine. Then you have to select boxes to inherit global site-packages to your new environment and make it available to all other projects. Leave them unselected.

Click Create on the bottom right and you will see the new project created:

You will also see a small Tip of the Day popup where PyCharm gives you one trick to learn at each startup. Go ahead and close this popup.

It is now time to start a new Python program. Type Cmd+N if you are on Mac or Alt+Ins if you are on Windows or Linux. Then, choose Python File. You can also select File → New from the menu. Name the new file guess_game.py and click OK. You will see a PyCharm window similar to the following:

For our test code, let’s quickly code up a simple guessing game in which the program chooses a number that the user has to guess. For every guess, the program will tell if the user’s guess was smaller or bigger than the secret number. The game ends when the user guesses the number. Here’s the code for the game:

1 from random import randint

2

3 def play():

4 random_int = randint(0, 100)

5

6 while True:

7 user_guess = int(input("What number did we guess (0-100)?"))

8

9 if user_guess == randint:

10 print(f"You found the number ({random_int}). Congrats!")

11 break

12

13 if user_guess < random_int:

14 print("Your number is less than the number we guessed.")

15 continue

16

17 if user_guess > random_int:

18 print("Your number is more than the number we guessed.")

19 continue

20

21

22 if __name__ == '__main__':

23 play()

Type this code directly rather than copying and pasting. You’ll see something like this:

As you can see, PyCharm provides Intelligent Coding Assistance with code completion, code inspections, on-the-fly error highlighting, and quick-fix suggestions. In particular, note how when you typed main and then hit tab, PyCharm auto-completed the whole main clause for you.

Also note how, if you forget to type if before the condition, append .if, and then hit Tab, PyCharm fixes the if clause for you. The same is true with True.while. That’s PyCharm’s Postfix completions working for you to help reduce backward caret jumps.

Now that you’ve coded up the game, it’s time for you to run it.

You have three ways of running this program:

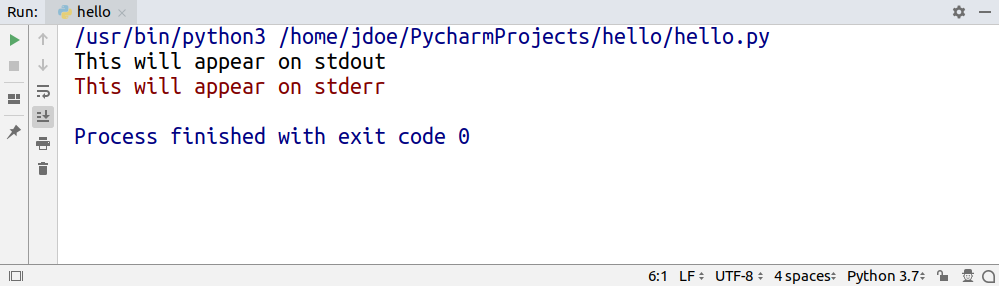

__main__ clause, you can click on the little green arrow to the left of the __main__ clause and choose Run ‘guess_game’ from there.Use any one of the options above to run the program, and you’ll see the Run Tool pane appear at the bottom of the window, with your code output showing:

Play the game for a little bit to see if you can find the number guessed. Pro tip: start with 50.

Did you find the number? If so, you may have seen something weird after you found the number. Instead of printing the congratulations message and exiting, the program seems to start over. That’s a bug right there. To discover why the program starts over, you’ll now debug the program.

First, place a breakpoint by clicking on the blank space to the left of line number 8:

This will be the point where the program will be suspended, and you can start exploring what went wrong from there on. Next, choose one of the following three ways to start debugging:

__main__ clause and choose Debug ‘guess_game from there.Afterwards, you’ll see a Debug window open at the bottom:

Follow the steps below to debug the program:

Notice that the current line is highlighted in blue.

See that random_int and its value are listed in the Debug window. Make a note of this number. (In the picture, the number is 85.)

Hit F8 to execute the current line and step over to the next one. You can also use F7 to step into the function in the current line, if necessary. As you continue executing the statements, the changes in the variables will be automatically reflected in the Debugger window.

Notice that there is the Console tab right next to the Debugger tab that opened. This Console tab and the Debugger tab are mutually exclusive. In the Console tab, you will be interacting with your program, and in the Debugger tab you will do the debugging actions.

Switch to the Console tab to enter your guess.

Type the number shown, and then hit Enter.

Switch back to the Debugger tab.

Hit F8 again to evaluate the if statement. Notice that you are now on line 14. But wait a minute! Why didn’t it go to the line 11? The reason is that the if statement on line 10 evaluated to False. But why did it evaluate to False when you entered the number that was chosen?

Look carefully at line 10 and notice that we are comparing user_guess with the wrong thing. Instead of comparing it with random_int, we are comparing it with randint, the function that was imported from the random package.

Change it to random_int, restart the debugging, and follow the same steps again. You will see that, this time, it will go to line 11, and line 10 will evaluate to True:

Congratulations! You fixed the bug.

No application is reliable without unit tests. PyCharm helps you write and run them very quickly and comfortably. By default, unittest is used as the test runner, but PyCharm also supports other testing frameworks such as pytest, nose, doctest, tox, and trial. You can, for example, enable pytest for your project like this:

pytest in the Default test runner field.For this example, we’ll be using the default test runner unittest.

In the same project, create a file called calculator.py and put the following Calculator class in it:

1 class Calculator:

2 def add(self, a, b):

3 return a + b

4

5 def multiply(self, a, b):

6 return a * b

PyCharm makes it very easy to create tests for your existing code. With the calculator.py file open, execute any one of the following that you like:

Choose Create New Test…, and you will see the following window:

Leave the defaults of Target directory, Test file name, and Test class name. Select both of the methods and click OK. Voila! PyCharm automatically created a file called test_calculator.py and created the following stub tests for you in it:

1 from unittest import TestCase

2

3 class TestCalculator(TestCase):

4 def test_add(self):

5 self.fail()

6

7 def test_multiply(self):

8 self.fail()

Run the tests using one of the methods below:

You’ll see the tests window open on the bottom with all the tests failing:

Notice that you have the hierarchy of the test results on the left and the output of the terminal on the right.

Now, implement test_add by changing the code to the following:

1 from unittest import TestCase

2

3 from calculator import Calculator

4

5 class TestCalculator(TestCase):

6 def test_add(self):

7 self.calculator = Calculator()

8 self.assertEqual(self.calculator.add(3, 4), 7)

9

10 def test_multiply(self):

11 self.fail()

Run the tests again, and you’ll see that one test passed and the other failed. Explore the options to show passed tests, to show ignored tests, to sort tests alphabetically, and to sort tests by duration:

Note that the sleep(0.1) method that you see in the GIF above is intentionally used to make one of the tests slower so that sorting by duration works.

These single file projects are great for examples, but you’ll often work on much larger projects over a longer period of time. In this section, you’ll take a look at how PyCharm works with a larger project.

To explore the project-focused features of PyCharm, you’ll use the Alcazar web framework that was built for learning purposes. To continue following along, clone the repo locally:

Clone Repo: Click here to clone the repo you'll use to explore the project-focused features of PyCharm in this tutorial.

Once you have a project locally, open it in PyCharm using one of the following methods:

After either of these steps, find the folder containing the project on your computer and open it.

If this project contains a virtual environment, then PyCharm will automatically use this virtual environment and make it the project interpreter.

If you need to configure a different virtualenv, then open Preferences on Mac by pressing Cmd+, or Settings on Windows or Linux by pressing Ctrl+Alt+S and find the Project: ProjectName section. Open the drop-down and choose Project Interpreter:

Choose the virtualenv from the drop-down list. If it’s not there, then click on the settings button to the right of the drop-down list and then choose Add…. The rest of the steps should be the same as when we were creating a new project.

In a big project where it’s difficult for a single person to remember where everything is located, it’s very important to be able to quickly navigate and find what you looking for. PyCharm has you covered here as well. Use the project you opened in the section above to practice these shortcuts:

As for the navigation, the following shortcuts may save you a lot of time:

For more details, see the official documentation.

Version control systems such as Git and Mercurial are some of the most important tools in the modern software development world. So, it is essential for an IDE to support them. PyCharm does that very well by integrating with a lot of popular VC systems such as Git (and Github), Mercurial, Perforce and, Subversion.

Note: Git is used for the following examples.

To enable VCS integration. Go to VCS → VCS Operations Popup… from the menu on the top or press Ctrl+V on Mac or Alt+` on Windows or Linux. Choose Enable Version Control Integration…. You’ll see the following window open:

Choose Git from the drop down list, click OK, and you have VCS enabled for your project. Note that if you opened an existing project that has version control enabled, then PyCharm will see that and automatically enable it.

Now, if you go to the VCS Operations Popup…, you’ll see a different popup with the options to do git add, git stash, git branch, git commit, git push and more:

If you can’t find what you need, you can most probably find it by going to VCS from the top menu and choosing Git, where you can even create and view pull requests.

These are two features of VCS integration in PyCharm that I personally use and enjoy a lot! Let’s say you have finished your work and want to commit it. Go to VCS → VCS Operations Popup… → Commit… or press Cmd+K on Mac or Ctrl+K on Windows or Linux. You’ll see the following window open:

In this window, you can do the following:

It can feel magical and fast, especially if you’re used to doing everything manually on the command line.

When you work in a team, merge conflicts do happen. When somebody commits changes to a file that you’re working on, but their changes overlap with yours because both of you changed the same lines, then VCS will not be able to figure out if it should choose your changes or those of your teammate. So you’ll get these unfortunate arrows and symbols:

This looks strange, and it’s difficult to figure out which changes should be deleted and which ones should stay. PyCharm to the rescue! It has a much nicer and cleaner way of resolving conflicts. Go to VCS in the top menu, choose Git and then Resolve conflicts…. Choose the file whose conflicts you want to resolve and click on Merge. You will see the following window open:

On the left column, you will see your changes. On the right one, the changes made by your teammate. Finally, in the middle column, you will see the result. The conflicting lines are highlighted, and you can see a little X and >>/<< right beside those lines. Press the arrows to accept the changes and the X to decline. After you resolve all those conflicts, click the Apply button:

In the GIF above, for the first conflicting line, the author declined his own changes and accepted those of his teammates. Conversely, the author accepted his own changes and declined his teammates’ for the second conflicting line.

There’s a lot more that you can do with the VCS integration in PyCharm. For more details, see this documentation.

You can find almost everything you need for development in PyCharm. If you can’t, there is most probably a plugin that adds that functionality you need to PyCharm. For example, they can:

For instance, IdeaVim adds Vim emulation to PyCharm. If you like Vim, this can be a pretty good combination.

Material Theme UI changes the appearance of PyCharm to a Material Design look and feel:

Vue.js adds support for Vue.js projects. Markdown provides the capability to edit Markdown files within the IDE and see the rendered HTML in a live preview. You can find and install all of the available plugins by going to the Preferences → Plugins on Mac or Settings → Plugins on Windows or Linux, under the Marketplace tab:

If you can’t find what you need, you can even develop your own plugin.

If you can’t find the right plugin and don’t want to develop your own because there’s already a package in PyPI, then you can add it to PyCharm as an external tool. Take Flake8, the code analyzer, as an example.

First, install flake8 in your virtualenv with pip install flake8 in the Terminal app of your choice. You can also use the one integrated into PyCharm:

Then, go to Preferences → Tools on Mac or Settings → Tools on Windows/Linux, and then choose External Tools. Then click on the little + button at the bottom (1). In the new popup window, insert the details as shown below and click OK for both windows:

Here, Program (2) refers to the Flake8 executable that can be found in the folder /bin of your virtual environment. Arguments (3) refers to which file you want to analyze with the help of Flake8. Working directory is the directory of your project.

You could hardcode the absolute paths for everything here, but that would mean that you couldn’t use this external tool in other projects. You would be able to use it only inside one project for one file.

So you need to use something called Macros. Macros are basically variables in the format of $name$ that change according to your context. For example, $FileName$ is first.py when you’re editing first.py, and it is second.py when you’re editing second.py. You can see their list and insert any of them by clicking on the Insert Macro… buttons. Because you used macros here, the values will change according to the project you’re currently working on, and Flake8 will continue to do its job properly.

In order to use it, create a file example.py and put the following code in it:

1 CONSTANT_VAR = 1

2

3

4

5 def add(a, b):

6 c = "hello"

7 return a + b

It deliberately breaks some of the Flake8 rules. Right-click the background of this file. Choose External Tools and then Flake8. Voilà! The output of the Flake8 analysis will appear at the bottom:

In order to make it even better, you can add a shortcut for it. Go to Preferences on Mac or to Settings on Windows or Linux. Then, go to Keymap → External Tools → External Tools. Double-click Flake8 and choose Add Keyboard Shortcut. You’ll see this window:

In the image above, the shortcut is Ctrl+Alt+A for this tool. Add your preferred shortcut in the textbox and click OK for both windows. Now you can now use that shortcut to analyze the file you’re currently working on with Flake8.

PyCharm Professional is a paid version of PyCharm with more out-of-the-box features and integrations. In this section, you’ll mainly be presented with overviews of its main features and links to the official documentation, where each feature is discussed in detail. Remember that none of the following features is available in the Community edition.

PyCharm has extensive support for Django, one of the most popular and beloved Python web frameworks. To make sure that it’s enabled, do the following:

Now that you’ve enabled Django support, your Django development journey will be a lot easier in PyCharm:

django-admin startproject mysite.manage.py commands directly inside PyCharm. For more details on Django support, see the official documentation.

Modern database development is a complex task with many supporting systems and workflows. That’s why JetBrains, the company behind PyCharm, developed a standalone IDE called DataGrip for that. It’s a separate product from PyCharm with a separate license.

Luckily, PyCharm supports all the features that are available in DataGrip through a plugin called Database tools and SQL, which is enabled by default. With the help of it, you can query, create and manage databases whether they’re working locally, on a server, or in the cloud. The plugin supports MySQL, PostgreSQL, Microsoft SQL Server, SQLite, MariaDB, Oracle, Apache Cassandra, and others. For more information on what you can do with this plugin, check out the comprehensive documentation on the database support.

Django Channels, asyncio, and the recent frameworks like Starlette are examples of a growing trend in asynchronous Python programming. While it’s true that asynchronous programs do bring a lot of benefits to the table, it’s also notoriously hard to write and debug them. In such cases, Thread Concurrency Visualization can be just what the doctor ordered because it helps you take full control over your multi-threaded applications and optimize them.

Check out the comprehensive documentation of this feature for more details.

Speaking of optimization, profiling is another technique that you can use to optimize your code. With its help, you can see which parts of your code are taking most of the execution time. A profiler runs in the following order of priority:

If you don’t have vmprof or yappi installed, then it’ll fall back to the standard cProfile. It’s well-documented, so I won’t rehash it here.

Python is not only a language for general and web programming. It also emerged as the best tool for data science and machine learning over these last years thanks to libraries and tools like NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn, Matplotlib, Jupyter, and more. With such powerful libraries available, you need a powerful IDE to support all the functions such as graphing and analyzing those libraries have. PyCharm provides everything you need as thoroughly documented here.

One common cause of bugs in many applications is that development and production environments differ. Although, in most cases, it’s not possible to provide an exact copy of the production environment for development, pursuing it is a worthy goal.

With PyCharm, you can debug your application using an interpreter that is located on the other computer, such as a Linux VM. As a result, you can have the same interpreter as your production environment to fix and avoid many bugs resulting from the difference between development and production environments. Make sure to check out the official documentation to learn more.